You may be able to “buy” a person’s back with a paycheck, position, power, or fear, but a human being’s genius, passion, loyalty, and tenacious creativity are volunteered only.

I’ve read a lot of business books in my life. It’s difficult to resist the urge, in reviewing any new business book, to situate it in a usual suspects lineup of other business books, to overlay this new book’s cliches and self-fulfilling case studies and available-for-consultancy-at-a-price corporate frameworks against other book’s cliches and self-fulfilling case studies and available-for-consultancy-at-a-price corporate frameworks. Inevitably we levy the same handful of criticisms: a judicious editor could cut the message down to a postcard1, the examples are as convenient as a 22-minute sitcom drama/resolution arc, and the writing is a type of snooze-fest I’d normally enact with a sleep-schedule resetting two-beer-and-a-swig-of-Nyquil nightcap.

But despite the popular wisdom, the devil really isn’t in the details with these books. It’s not so much the wisdom they dispense but rather the way it makes us think about how we work, why we make the choices we do, and how we can be more effective in those choices. Business books are valuable to me because they offer me a prism to reflect upon my work, to inject some intentionality and deliberateness into a day-to-day that is largely spent reacting, jumping from incident to incident, a day-to-day where I am expected to furnish judgments with little to no context, dealing with human problems of frustration or burnout or incompatibility or miscommunication. Learning is reflection, and business books can be a forcing function for that reflection, giving us some sort of ubiquitous language to scaffold a small group of archetypal problems. And at curtain’s close, most of the problems I encounter (and I suspect most others as well) start and end with communication.

The leader-leader structure is fundamentally different from the leader-follower structure. At its core is the belief that we can all be leaders and, in fact, it’s best when we all are leaders. Leadership is not some mystical quality that some possess and others do not. As humans, we all have what it takes, and we all need to use our leadership

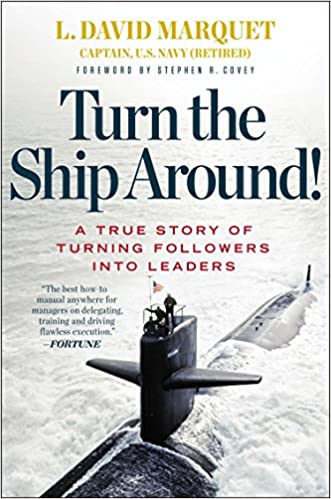

David Marquet, in Turn the Ship Around!, outlines his vision for how a leader should operate. Marquet advocates for pushing control down into all levels of an organization, to “shift focus from avoiding errors to achieving excellence”, to move beyond how we viewed leadership in the past, built on a cult of personality and the charisma of a single dictatorial leader in charge. Marquet uses his time as captain on the Los Angeles-class submarine the Santa Fe as a framing device for his dispensed wisdom, each chapter running a handful of pages and covering a small topic via a parable-like anecdote of some problem and subsequent resolution on the Santa Fe.

If that description sounds dismissive, it isn’t meant to be. Business books aren’t the apogee of human culture2. They are didactic, read quickly or skimmed entirely. As much as a business book can be a page-turner, Marquet’s book is that. It’s like Jack Reacher moonlighting as an actuary. There’s a reason there are so many submarine movies. A submarine is a narrow stage and there is no escape, the dramatic tension contouring to the shape of the hull. There is a grand, mystical, and unrealized “out there” that matters little to what is happening “in here”, and “in here” every decision matters, every mistake could spell death at best, world war at worst.

The framing device is effective, and the questions to consider at the end of each chapter are legitimately good, especially if actually considered. Marquet’s book doesn’t commit the cardinal sin of most business books, which is a narrow-minded dogmatism in the rules it outlines. This is a book that takes a very simple idea, that control should be pushed down in any organization and that this control needs to be tent-staked to the ground via competence and mission clarity, and applies it to real-life, plausible3 scenarios aboard a 2 billion dollar submarine carrying enough materiel to decimate any number of large metropolitan cities in an instant.

While the book is geared towards executive leadership, you can also apply these principles at any level. There are interesting tidbits about building resilient organizations, and establishing specific, measurable goals, building followers into leaders, etc. All bread and butter business book fodder, but told in a compelling way.

All in all, the book was a nice mesh of Edward Demings, OKRs, Simon Sinek, and Multipliers put into a blender and turned into a 272 page read that’s worthy of an afternoon or two.

Footnotes

-

I’m no Keynesian, but I’d imagine the market for books, however emaciated it’s been rendered over the last 25 years by an increasingly reluctant readership, is still outpacing the postcard market, hell, even the pamphlet market. Research pending. ↩

-

That said, I’m sure there are some real sickos that put things like Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People on best literature lists, because of it’s impact or something. ↩

-

The best verisimilitude any of these books can aspire to is “plausible”. I don’t know if it’s the fact that I grew up without and then with the internet, but I default to the notion that nothing really happens, or at least not like the way people say it does; reality is diffracted and refracted through so many competing biases and human limitations and interests as to be basically impossible to objectively retell. Add in the clear economic interest any business book writer has for their particular ideology and there’s no chance any example bandied about to justify said ideology’s efficacy by said business book writer actually happened like they said it happened. But this isn’t the scientific method, and most of these business books make rhetorical arguments rather than scientific ones, so I suppose it’s enough for us to think that the events outlined could happen. ↩